Men Are Worthless Especially For Young Women You probably all know about the White Feather campaign orchestrated by the feminists during World War One that was designed to shame men into signing up for the military, but the first time that I realized that men were considered to be almost completely worthless and disposable was

Men Are Worthless

Especially For Young Women

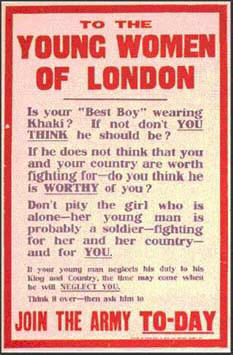

You probably all know about the White Feather campaign orchestrated by the feminists during World War One that was designed to shame men into signing up for the military, but the first time that I realized that men were considered to be almost completely worthless and disposable was at about age seven.

You probably all know about the White Feather campaign orchestrated by the feminists during World War One that was designed to shame men into signing up for the military, but the first time that I realized that men were considered to be almost completely worthless and disposable was at about age seven.

There was a programme on the radio about the Napoleonic Wars – or something similar. And the speaker was explaining some battle manoeuvre – some stratagem – whereby General Whoever ordered a few hundred infantrymen to charge up the hill simply in order to figure out where the enemy’s strengths lay.

There was no hope, or intention, that any of these soldiers would survive. Or that they would be rescued in any way. Their lives were simply expended in order to provide the General with some information that he was keen to have.

Nowadays, I would see this as an historical example of EXTREME ‘oppression’ against the male gender, but, at age 7, it was simply just a sickening shock to discover how worthless the lives of these men, and, hence, the male gender, and me, seemed to be.

This was confirmed further when I discovered not much later that such wastage of life in similar circumstances was not actually confined to the distant past, but that this kind of thing also went on in WWII.

In other words, this somewhat unpalatable disregard for the lives of one’s very own soldiers – which made me gulp whenever I thought of it – had not been abolished.

Generals were, even then, still at liberty to employ such methods simply to help them with their calculations.

The soldiers whom I saw occasionally on the streets of London – and on trains – could actually be sent up hills and straight to their deaths at any time if an important someone simply wanted to do a calculation.

It haunted me.

war was much more about numbers than about lives

Because my disturbance at all of this impelled me to inquire about such things, I also soon discovered that war was much more about numbers than about lives. And so, for example, the General might send a thousand troops into battle knowing that very few of them were likely to survive it.

“That bridge is worth it, even if it costs 700 men.”

And I also heard how in the first stages of the huge allied invasion of France on D-Day – June 1944 – in the fight against Hitler in WWII, a few hundred men were flown behind enemy lines in gliders in order to help prepare the way for the invasion, and that fewer than 3 out of 10 were expected by the generals to survive.

“You are going out there to die.”

“You are going out there to die.”

I began to understand, simplistically, the reasons and the justifications for such things – “Well, that’s war. What else can you do?” – but that didn’t really solve the problem. It didn’t quite get to the points that disturbed me.

And there were quite a few of them!

The first was the fact that, no matter what the reason, the men who were being sent to their deaths were losing all that they had. All that they were. There was absolutely nothing else that they could give. They gave it all.

And many had little choice.

Secondly, and almost as chillingly, these men were little more than pawns in the eyes of those who studied the maps. And the same was true for much of the country. There was some sadness, for sure, when large numbers died. But, for the most part, they were just numbers.

It was only those who were directly and personally affected by the tragedies that befell those men who were close to them, who were actually able to appreciate some small part of their terrible experiences.

these men were just numbers.

For the rest of the country, well, these men were just numbers.

Throughout WWII, for example, London was a popular place to where people flocked in order to enjoy the nightlife. So, these people were hardly riddled or incapacitated with grief over the war dead, were they?

They were going out and having fun!

Yes, Yes, I know that people have got to ‘let go’ and enjoy themselves – and put any thoughts about the dead and injured soldiers behind them – BUT THAT’S MY POINT!

They forgot about them!

Thirdly, of course, it was quite clear to me that those destined to die were chosen – or they volunteered – mostly on the basis of their gender. There was, therefore, something clearly very different about men and women in this respect.

Thirdly, of course, it was quite clear to me that those destined to die were chosen – or they volunteered – mostly on the basis of their gender. There was, therefore, something clearly very different about men and women in this respect.

They were worth less.

Considerably less.

Further, they were expendable in the most horrible of ways.

While others danced and forgot about such things.

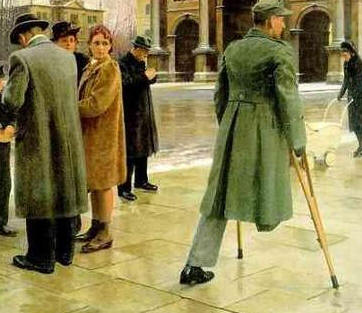

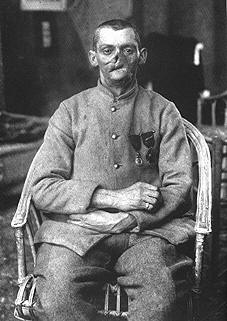

And then, of course, there were all those limbless and/or disfigured men whom I saw so often on the streets in those days. Their shapes, their outlines, and the sight of their jackets or trousers being pinned up where there was no limb to fill the fabric, were all imprinted on my mind; not just visually, but in what it all meant for the ex-soldiers who, even many years after the end of any war, were paying such a terrible price.

It was absolutely clear that these men were still paying heavily, in some way, for every minute that they were awake – and probably when they were asleep too.

It was absolutely clear that these men were still paying heavily, in some way, for every minute that they were awake – and probably when they were asleep too.

You could see this in their eyes.

You could also see this in their sad demeanors, in the ways that they had to struggle to deal with even the simplest of movements, and in the loss of dignity that many clearly succumbed to as they grew older, more debilitated, more distanced and more forlorn.

At a later age, I often used to think of how disheartening and soul-destroying it must have been for those who returned in such a damaged state to discover that their girlfriends had found someone else while they were away – or could not now face them with their injured bodies, their absent parts and their disfigurements.

At a later age, I often used to think of how disheartening and soul-destroying it must have been for those who returned in such a damaged state to discover that their girlfriends had found someone else while they were away – or could not now face them with their injured bodies, their absent parts and their disfigurements.

And I wondered how they must have felt at constantly having to present their lessened selves to the people who would have to deal with the consequences of such things.

To leave one’s loved ones as a strong, brave and handsome soldier, and to return as a seemingly unattractive helpless burden – as it must have seemed to some – must have been psychologically devastating.

To leave one’s loved ones as a strong, brave and handsome soldier, and to return as a seemingly unattractive helpless burden – as it must have seemed to some – must have been psychologically devastating.

But, yes. I was about 7 when I first realized that I belonged to the disposable gender. And most of what I have seen ever since then has merely confirmed this notion.

But, yes. I was about 7 when I first realized that I belonged to the disposable gender. And most of what I have seen ever since then has merely confirmed this notion.

But I’m not complaining about the fact that our men went to war. Nor, particularly, that it was men rather than women who ended up on the battlefield.

But I’m not complaining about the fact that our men went to war. Nor, particularly, that it was men rather than women who ended up on the battlefield.

I’m not sure how we could have done things differently – given the circumstances, the requirements, and the times.

But, when feminists continually complain to the world about how ‘oppressed’ were women in the days of the generation that preceded mine, and I think of the generals sending tens of thousands of men to their certain deaths simply in order to do their calculations, or when I think of those men who had to continue to live in a permanently-handicapped state for the rest of their lives, I have arising within me – from somewhere – an almost uncontrollable urge to spit at them.

1914

1914

(Also see Other letters from home had a nastier edge. ‘I’ve left you for a proper soldier,’ more than one Prisoner of War was told by his wife or girlfriend. ‘I’d rather be with a fighting man than with one who gave up.‘ Tony Rennell)

Not Forgotten on BBC 2: Ian Hislop explores events following Armistice Day, as Britain’s five million surviving soldiers returned home after World War One. Although promised a land fit for heroes, they faced widespread unemployment and poverty, while physical disability and psychological trauma meant their lives would be changed for ever.

Not Forgotten on BBC 2: Ian Hislop explores events following Armistice Day, as Britain’s five million surviving soldiers returned home after World War One. Although promised a land fit for heroes, they faced widespread unemployment and poverty, while physical disability and psychological trauma meant their lives would be changed for ever.

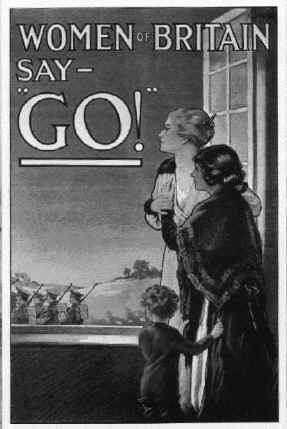

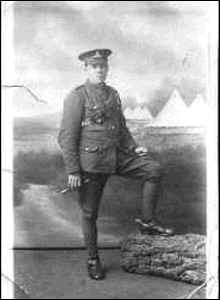

John Kirkwood, a gunner in the Royal Field Artillery, joined up after being sent a white feather (implying he was a coward). He was killed at the Somme on 26 July, 1916. Photo: C Cooper

John Kirkwood, a gunner in the Royal Field Artillery, joined up after being sent a white feather (implying he was a coward). He was killed at the Somme on 26 July, 1916. Photo: C Cooper

Also in 1916, while the suffragettes were moaning about the lack of ‘the vote’ for women (and also handing out white feathers to those men who were not wearing military uniform) 20,000 British men were killed on the very first day of the Battle of the Somme, and a further 125,000 British men were killed during the next five months in this battle alone.

But, according to these suffragettes, it was women who were being oppressed.

Afghanistan Veteran 2009

Afghanistan Veteran 2009

1 Comment

Jb

August 21, 2021, 7:37 pmLmao that was hilarious.

REPLY